I went to a very posh tasting at the Dorchester last night that would not normally be the subject of this blog but for the remarkable fact of a French female sommelier, Estelle Touzet - head sommelier at the 3 starred Le Meurice, no less - serving up a New Zealand biodynamic wine (Felton Road's 2009 Bannockburn Pinot).

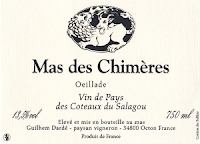

In fact of the four wines she showed - only one was French (Coumbe del Mas) - and from the Roussillon not one of the more prestigious wine areas.

It really shows how fast the restaurant world is changing. It's inconceivable that one of the so-called 'palaces' as Paris's most prestigious hotels are called, would have had a female head sommelier or shown wines of this type at a press event even five years ago. Touzet reckons that around 200 wines from her 1100 strong list are biodynamic, possibly more as many producers choose not to certify . . .

I also gather (from my colleague Richard Hemming via Twitter) that Anne-Claude Leflaive has launched a new biodynamic négociant business, Leflaive et Associés which will be buying in fruit from biodynamic growers. Further proof, if proof were needed, that biodynamics is becoming big business.

And what did the wine taste like? Ah, forgot to mention that. Elegant, mineral, quite smokey - I thought it might be a mourvèdre, without the lush fruit that tends to typify Central Otago pinot. But, interestingly, it was a root day. A great match though with a 'bouchée' of rare beef with celeriac rémoulade and a lot of black pepper which actually restored some of the fruit to the wine. More on my matchingfoodandwine website tomorrow.